“Myths are made for the imagination to breath life into them.” Albert Camus

“The trouble with the world is not that people know too little; it’s that they know so many things that just aren’t so.” Mark Twain

Introduction: Parkinson’s continues to expand in numbers of people worldwide and firmly stands as the second most common neurodegenerative disorder. In 2022, I posted a blog entitled “Fifteen Myths and Common Misconceptions About Parkinson’s” (click here). Here are presented fifteen additional myths and common misconceptions about Parkinson’s, and they are grouped into the following categories: General Features of Parkinson’s, Symptoms of Parkinson’s, and Treatment of Parkinson’s.

“Myths are public dreams, dreams are private myths.” Joseph Campbell

General Features of Parkinson’s:

Parkinson’s drastically shortens your life/longevity.

It is true that Parkinson’s is a chronic disease, and in some people, it may lead to a shortened life span. The two main reasons for a shortened life in Parkinson’s patients relate to complications from falls and injuries and dysphagia (difficulty in swallowing). As motor skills decline over time, this increases the risk of falls. Difficulty with swallowing can lead to aspirational pneumonia, which poses a real risk of mortality in people-with-Parkinson’s (PwP). However, with proper care and management, many people live for many years following their diagnosis. And with appropriate training and assistance, steps can be taken to try to reduce the risk of falling and dysphagia.

The symptoms of Parkinson’s are only related to the loss of dopamine.

While Parkinson’s is primarily characterized by the loss of dopaminergic neurons, abnormalities in other neurotransmitters occur. Yes, the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra contributes much to motor dysfunctions; there is evidence of disrupted function of other neurotransmitters, including acetylcholine, norepinephrine, and serotonin. Thus, this consortium of neurotransmitters anomalies contribute to the motor- and non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s.

The presentation of Parkinson’s is limited to a single side of the body.

The initial presentation of the motor defects in Parkinson’s occurs on one side of the body. Eventually, however, both sides will be affected. Think about it this way, there are two sides to the substantia nigra, and the initial impact of Parkinson’s is focused on one side. Since Parkinson’s is a progressive disorder, with time and advancement of the disorder, both sides of the substantial nigra become involved. Thus, symptoms just thought to be seen in the original side of the body now have them on both sides. Usually, the symptom expression is not as severe as the original unilateral side. The two-sided manifestation of symptoms is essential for the physician to understand the disorder’s progression and devise ways to prevent the transition from unilateral disease to bilateral disease. Keep in mind that exercise may slow the progression to prevent bilateral disease.

Patients with Parkinsonism are just patients not fully diagnosed with Parkinson’s.

An incorrect statement. This comment challenges some essential issues related to disease classification and symptoms that lead to a diagnosis. We use the term “Parkinsonism” to describe someone with symptoms that relate to someone having tremors, slowness of movement, rigidity, and postural instability. Here is the key point: all patients diagnosed with Parkinson’s have Parkinsonism; however, not all patients with Parkinsonism have Parkinson’s. Diagnosing someone with Parkinson’s requires the presence of two of the four symptoms above. Physicians are faced with complex diagnostic issues with someone with Parkinsonism. They are classified as Atypical Parkinsonism, and they include Multiple System Atrophy (MSA), progressive Supranuclear Palsy (PSP), and Corticobasal Degeneration (CBD). Unlike Parkinson’s, Atypical Parkinsonism does not respond well to carbidopa-levodopa; thus, managing the disorder is difficult.

The first written description of the disease resembling Parkinson’s was by the English physician James Parkinson in 1817.

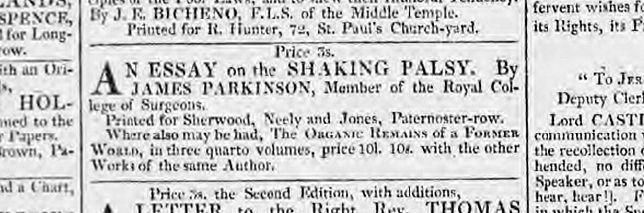

It is true that this was the first English version description of the disease and likely the first peer-reviewed medical publication describing this disorder. However, there is a historical precedence that Parkinson’s-like disorders were described centuries ago by Ayurvedic physicians. I mentioned recently in the blog post “Potential Benefit of Ayurvedic Turmeric, Ginger, and Ceylon Cinnamon for Treating Parkinson’s” (click here), “In ancient literature, an Ayurvedic disease called “Vepathu” was characterized by shaking or trembling. During the 7th century AD, an Ayurvedic physician named Madhava portrayed Vepatha as a whole body and hand tremor, namely, “Sarvangkampa” and “Shirokampu.” In the 12th century AD, the term “Kampavata” replaced Vepathu.” What makes the essay by James Parkinson so valuable is the detailed description of the patients he followed and the thoroughness of his description. Our friends at the “Science of Parkinson’s” located the first time the Parkinson’s essay was published and marketed to the public (click here).

“We can get so wrapped up in our own misconceptions that we miss the simple beauty of the truth.” Deb Caletti

Symptoms of Parkinson’s:

Chronic pain affects only a small percentage of people with Parkinson’s.

Not true. Chronic pain affects a large number of PwP; in fact, it has been calculated to occur in 45-85% of individuals with the disorder. When considering pain in PwP, there are four significant types of pain: musculoskeletal pain (usually resulting from postural changes and rigidity), dystonic pain (caused by abnormal contractions and postures), neuropathic pain (includes symptoms like tingling or a burning sensation); and central pain (devastating and challenging to manage and treat, likely associated with a dysfunction in the pain processing pathways of the brain).

The non-motor symptoms are more related to other diseases and not Parkinson’s.

This is an interesting and vital misconception. While non-motor-related symptoms occur in various health disorders, they are included in Parkinson’s. Importantly, they can often present themselves prior to motor dysfunctions. Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s can overlap with other diseases/organs; however, they are important in the management of someone’s Parkinson’s. Examples of three types of non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s include cognitive impairment (difficulties with memory, attention, and executive functions that can lead to dementia), mood disorders (such as anxiety and depression), and sleep disorders (like insomnia and REM sleep behavior disorder).

Tremor-dominant forms of Parkinson’s show faster rates of progression than the non-tremor dominant forms of Parkinson’s.

Recent evidence supports the opposite in that non-tremor dominant forms of Parkinson’s progress faster than tremor-dominant forms. A key issue for clinicians and those who study Parkinson’s is to better understand and manage the long-term prognosis of Parkinson’s. There are two major ‘types’ of Parkinson’s, broadly defined as Tremor-Dominant (TD) and Postural Instability and Gait Difficulty (PIGD). TD Parkinson’s has a resting tremor, and this sub-type is associated with less-severe non-motor symptoms and usually has a good medication response. The PIGD Parkinson’s subtype has a more significant challenge in balance and walking. They often progress more rapidly in terms of overall disorder severity and development of motor complications. Realizing that each PwP is uniquely different, placing everyone in one or two categories is hard. Longitudinal studies have shown that the presence of a tremor showed a slower rate of progression of symptoms compared to the PIGD group.

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) is not involved in the symptoms of Parkinson’s.

Not true. The ANS is frequently found to be malfunctioning in many different ways in about 70-80% of PwP. The cause of the ANS-related problems is thought to be caused by degeneration of the ANS ganglia and brainstem/hypothalamic nuclei. This unfortunate alteration in the ANS leads to several major issues, which can include cardiovascular problems, including orthostatic hypotension (low blood pressure upon standing), sexual dysfunction, sleep and urinary disorders, and gastrointestinal issues like constipation. Each one of these issues can cause a major change in the PwP’s quality of life. And in many areas, more than one type of ANS anomaly occurs, which contributes to the complexity of managing Parkinson’s.

There are more motor-related symptoms than non-motor-related symptoms.

Not true. Motor symptoms affect your movement and balance. The primary motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease (PD) are tremors, rigidity (stiffness), bradykinesia (slow movement), and postural instability (balance problems). The breadth and impact of non-motor symptoms are simply daunting to describe. The non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s do not modify movement. Breaking down the non-motor symptoms as follows describes this breadth of differences from the motor symptoms: mental health and cognitive issues (depression and anxiety; apathy; cognitive difficulties; psychosis; and dementia); autonomic dysfunction (orthostatic hypotension; constipation; bladder and bowel problems; sweating problems: and sexual dysfunction; and sensory and other Issues (loss of smell; sleep problems; fatigue; pain; swallowing and speech defects; and drooling.

“Misconceptions play a prominent role in my view of the world.” George Soros

Treatment of Parkinson’s:

You should wait several years after the diagnosis to begin treatment with carbidopa-levodopa.

There are two arguments described here. First, the gold standard of treatment for Parkinson’s is carbidopa-levodopa. While it does not slow the progression of the disorder, it is the most effective drug. Second, there is a time-dependent issue related to the long-term use of carbidopa-levodopa that results in dyskinesia. Thus, many patients are initially treated with a dopamine agonist instead of carbidopa-levodopa. Over time, patients are switched to carbidopa-levodopa. Of course, there are well-known side effects of dopamine agonists, which are based on compulsive behavior issues.

Three processes are happening in Parkinson’s as we age. There is the initial dopaminergic nigral neurodegeneration. This is the 20-60% loss of dopaminergic neurons that precedes apparent motor dysfunction. This phase is prime time for carbidopa-levodopa to be most active in restoring motor function. The second phase is the continued progression of the dopaminergic nigrostriatal neurodegeneration. It is at this time one sees carbidopa-levodopa becoming less efficient. The incidence of dyskinesia relates more to the age of Parkinson’s symptoms rather than Parkinson’s duration. The third aspect relates to age-dependent parkinsonism (approaching 80 years old and beyond). This leads to senile extrapyramidal motor problems (slowness, stooped posture, shortened stride) happening with old age. And these old age-related symptoms do not respond to carbidopa-levodopa. Thus, we all fit within these 3 patterns of dopaminergic neuron degeneration; however, we each have our own distinct decay signature. My thought is, why wait? Go ahead and start carbidopa-levodopa when diagnosed, and enjoy its therapeutic effect. The dyskinesia may become evident in five years; 10 years later, it differs for each PwP. It would imply that this is not a change in how carbidopa-levodopa works, it is how the changes within each of us as to how we are able to use carbidopa-levodopa.

Pharmaceutical companies are more likely to turn to Parkinson’s research, partly due to the surge in patients since the COVID-19 pandemic.

Unfortunately, this is not true. Several large pharmaceutical companies have stopped drug development work on neurodegenerative disorders. They partly make decisions on where the money is to be made. One example, there are more than 38 million people in the USA with diabetes while there are ~1 million living with Parkinson’s. There are simply a lot of challenges for pharmaceutical companies to develop new drugs and then test them to be effective at managing the progression of Parkinson’s. However, saying this, other companies continue to seek ways to reinvigorate their neurology work. When one considers the high cost and high failure rates of, most drugs are features critical to most companies. With an aging population and a growing prevalence of the number of people with Parkinson’s, several companies are rethinking their strategies to find, develop, test, and advance new treatment modalities for Parkinson’s. There is a need for the development of new drugs to treat Parkinson’s, and now is the time for the Parkinson’s community to remain informed, educated, and committed to encouraging companies to work on Parkinson’s.

Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) surgery is considered an experimental procedure.

This is not true, although it is true that the mechanism of how DBS works remains unclear. DBS was once marked as experimental; however, the technique is now widely used and FDA-approved. DBS is used when patients are no longer able to control motor symptoms with drug therapy. A power source is placed in the chest and delivers electrical stimulation to specific regions of the brain. DBS can reduce symptoms like rigidity, tremor, and bradykinesia. Significantly, DBS does not slow down disease progression. Furthermore, finding a neurosurgeon with much prior experience makes a big difference, as does preoperative planning to where the electrode will be placed, which can help optimize the results of DBS surgery.

Exercise continues to work well in rodent models for managing Parkinson’s, but not so much in humans. This comment is absolutely false. Over the last 5-8 years, clinical trials in humans has shown that we can improve our motor-related scores and can, with due diligence, slow the progression of the disease. The issue with animal models is that we ‘make’ the mouse to have Parkinson’s. It takes only a few hours to complete the transition. When you treat the mouse with treadmill exercises, they seemingly run off the disease. And remember, these are inbred mice, so genetically, they are identical, and they have exactly the same disease as another mouse. Of course, in humans, 10 people with Parkinson’s are 10 different diseases to test. These statements may be an oversimplification of the issue. Still, it is excellent news that strenuous exercise alters the trajectory of Parkinson’s to some extent. The key for me is that you do as much exercise as possible, your body and mind will appreciate it, and exercise will improve your quality of life, while your Parkinson’s will want you to be sedentary.

How I look is how I feel.

This is an important concept in Parkinson’s, significantly where our posture and facial expression can change as the disorder progresses. This implies that individuals with a positive self-image will have higher self-esteem levels and less emotional distress. Unfortunately, a chronic disorder like Parkinson’s can lead to feeling embarrassed or inadequate, thus perpetuating a negative self-perception. To try to improve this low self-opinion, one could obtain therapy aimed at improving negative self-perceptions, join a support group with members experiencing the same issues, and exercise to promote body movements can enhance physical health.

An alternative idea exists when thinking of the “mask” of Parkinson’s and someone’s inability to smile. A PwP may feel relatively well and happy one day on the inside. Still, their mask hides any positive expression and could make an observer think they are sad, unhappy, or disconnected emotionally.

“Myths which are believed in tend to become true.” George Orwell

The Complex Nature of Parkinson’s: Parkinson’s is not an easy disease because it is constantly trying to change you—consider the complexity within the roles of dopamine highlights motor-derived dysfunctions. Then, you add the breakdown of the other neurotransmitters and the role of the ANS to gain some hints about the devastating effect of the non-motor defects. We will each have our own unique disease, which will follow its own pattern of neurodegeneration. Ultimately, the expression of Parkinson’s by each individual promises to give one a new appreciation of the difficulty of living with Parkinson’s.

The complexity of Parkinson’s leads to many myths and misconceptions about the disease. Hopefully, the 30 points raised in the current and a past blog post entitled “Fifteen Myths and Common Misconceptions About Parkinson’s” (click here) have partially clarified the muddled waters concerning some concepts behind this complicated disorder.

“Myths are so intimately bound to culture, time, and place that unless the symbols, the metaphors, are kept alive by constant recreation through the arts, the life just slips away from them.” Joseph Campbell

Cover Photo Image by Syed Irfan from Pixabay